Lives of Unforgetting

A downloadable ebook

Lives of Unforgetting: What We Lose in Translation When We Read the Bible, and A Way of Reading the Bible as a Call to Adventure

When you translate radical or subversive texts into the language of Empire, you eventually get Imperial texts. In this book, we will take a close look at what has been lost.

At this store, the book is available in MOBI (kindle) and EPUB (nook, tablet, smartphone) editions.

This book is also available in PAPERBACK at:

Direct from the author | Bookshop | Amazon | Barnes & Noble Online

What You'll Find in This Book

The ancient Greek word for “truth” means unconcealing or unforgetting. Yet today many ideas and stories that were once critical to how early Christians understood, practiced, and defended their faith often remain “hidden in plain sight” in our Bibles. These ideas are concealed from us by the distance between languages, between eras, and between cultures—yet they are so worth unconcealing and unforgetting. In this book, discover:

- The forgotten women who co-founded Christianity

- Whether the first-century church thought there was a hell

- What happens when you realize that in Greek, faith is a verb

- Why gender in the Bible is more complicated than we think

- Which concepts our modern tradition takes for granted that would have been alien to the original readers (like homophobia)

We have also forgotten that to read the Bible is to receive an invitation to adventure—to encounter the impossible, to move mountains, to walk on water. Instead, we have been taught to read the Bible tamely, to make no choices, to risk no questioning of our tradition. What would happen if we took the adventure? If we readers walked out into the wilderness toward God, leaving home far behind? If we stepped out of the boat of our received tradition, out onto the crashing waves?

Let’s find out.

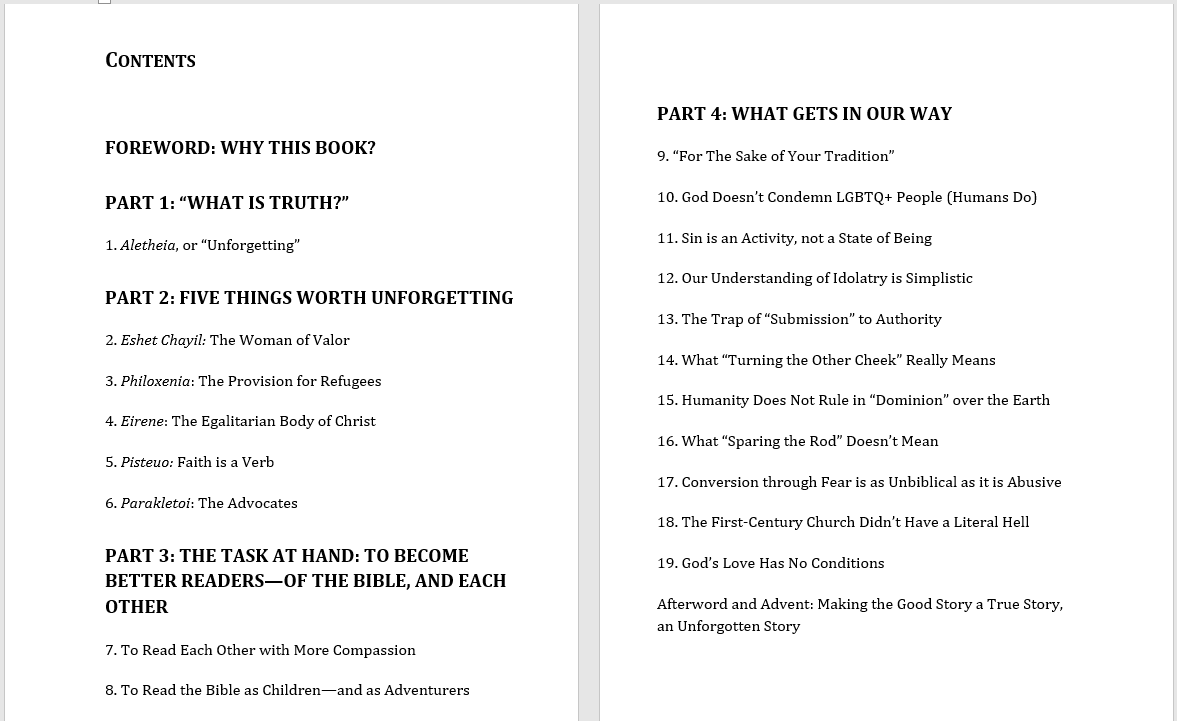

Table of Contents

Excerpt

Misogyny walks around wearing religion’s clothes, and this is a great frustration to me because our holy texts are packed with stories of relentless, brave, daring women whose lives we conveniently overlook, whose stories we either fail to tell at all or tell very badly. And because I love their stories, and because this is a book about what (and who) gets overlooked in traditional translations and interpretations of the Bible, I want to open this chapter with a shout-out to the bold women of the Bible; may they be unforgotten. My admiration to Rizpah, who guarded the bodies of her children from wild animals and carrion beasts all night, defying the king and his soldiers; to Deborah, a middle-aged prophet who settled the court cases no one else could and led armies against an invading force; to Jael, who drove a tent peg through a dude’s head; to Mary, who fled to another country to keep her baby from being killed and then later after returning raised her child in a small town where everyone thought she was a “slut”—and raised him so well that the world still reveres his name (and hers) to this day; to Vashti of Persia, who was commanded by the king to show up naked and wearing only her crown to “display her beauty” for the entertainment of his guests—and who told the king, “No”; to Mary Magdalene, who endured the disbelief of many when she told of what she saw, but who didn’t disbelieve herself; to Judith, who seduced an invading general in order to get close enough to chop off his head; to a woman whose name we don’t remember, who stood on the wall of a starving city and killed the tyrant Abimelech by chucking a brick down at his head; to Miriam, the first of the prophets of the Children of Israel after their departure from Egypt, singing on the shores of the Red Sea moments after seeing her people’s enemies crushed under falling water; to Huldah, who commanded such respect that when the lost sacred texts were discovered, the priests handed them over to her and said, “Please interpret these for us, Huldah”; to Dorcas the healer, who refused to leave those dying of fever, no matter the contagion; to the Queen of Sheba, who traveled a continent to meet people of learning and establish trade deals for her nation; to Joanna and Susanna, who funded Jesus’s ministry and had a great deal to do with the early disciples not starving on the road; to Prisca, Mary, Apphia, Julia, Phoebe, Junia, Chloe, Euodia, Syntyche, Tryphena, Tryphosa, and others, apostles and leaders of the early church; to Mary sister of Martha who studied with a rabbi, and to Martha sister of Mary who did the dishes and cooked so she could; to the unnamed, brave woman who suffered continual bleeding and a life of being outcast and untouchable by her community and who yet found the courage to seek out a miracle worker and commit what her community would treat as an unforgivable act: to touch him; to Anna, who spent nearly a century prophesying in the Temple; to Shiprah and Puah, both just and cunning (who may have been either individual midwives or, as rabbinical scholars have suggested, sisterhoods of midwives), who refused to slay Hebrew infants and who, when questioned by Pharoah, used the monarch’s own racial bigotry to deceive him: “We tried to carry out your command, O Pharoah, but the Hebrew women are such animals,” they reported blithely, “that they squat and give birth before we can even get there!”; to Jochebed, who sent her baby down a river in a basket rather than let him be found by genocidal soldiers; to Abigail, who prevented a massacre; to Dinah, who got blamed for one; to Hadassah (Esther), who stopped a genocide from happening on two continents; to Tamar, who found an unusual, daring, and quite horrifying solution to her father Judah’s neglect in leaving her unprovided for and starving; to the witch at Endor, visited in the night by a king who had sworn to exterminate everyone like her, yet so moved by their common humanity that she cared for him and fed him after he fainted with terror and exhaustion at a vision; to Delilah, who outwitted and captured her people’s greatest foe; to Mahlah, Noa, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah, who marched up to Moses in the desert and said, “We don’t have a brother, and we want to inherit our father’s property”; to the eshet chayil (the “woman of valor” who “stretches out her hands to the needy”) who fed Elijah when he staggered, exhausted and starving, to her doorstep, though she had only a single cake of bread left in the house; to the Shulammite, who loved a foreign king, survived prejudice and brutality, and chose love over fear, even against all the terror-pressure of past trauma; to Bathsheba, so often remembered as a victim of either rape or seduction, so often reduced in our retellings to a momentary plot device, but whose actual story lasted decades and who successfully maneuvered her only son to the throne; to Naomi, who lost so much to famine and tragedy, yet found joy again; to Ruth, who immigrated to a land hostile to her people, yet stayed and kept her mother-in-law and herself fed and alive, daily risking rape or worse in the fields where young men followed the vulnerable, “exotic” immigrant gleaners at a near distance; to Lydia of Thyatira, the businesswoman who funded Paul’s missionary work in Macedonia because a story he told once lit her heart on fire; and to so many, many others who lived such stories.

Unforgetting The Woman of Valor in the Bible

We’ve frequently forgotten or neglected the tales of these women. Yet their stories are right there in our Bible, as if hidden in plain sight. They are a remainder that has been left out of our traditional interpretations, these stories that fill the Bible but that we have neglected to read or attend to. The names and stories of these women are among the things in this book that I wish for us to unforget—that we must unforget, if we are to take, rather than avoid, the adventure of reading the Bible.

Today we read the Bible in English, a language deeply influenced by Latin, and we read it in translations informed by an interpretive tradition dating back to the long centuries when the Bible was available to Europe primarily through the Vulgate, a late fourth-century Latin translation. But the Bible was not written in Latin by Romans. It is a library of texts (66 books in Protestant Bibles, 73 books in Catholic Bibles, 81 in Greek Orthodox Bibles) in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. These are languages that operate very differently from Latin—or English. And these texts were set down within cultures that faced different tensions from our own. Reading the Bible at a distance of 2,000 years, we emphasize different things than the Bible’s first readers would have. Some things we leave out of our tradition altogether—like that list of valorous women.

There is another obstacle, too, besides the gaps between languages and cultures, and it has to do with the relationship between the Bible and power. Many sections of the Bible were written originally by people who had little power in their societies. Paul wrote letters under house arrest; some of the Psalms were written by a people living in captivity; Nehemiah wrote his account of the restoration of Jerusalem while continually on the brink of civil war; Jeremiah’s prophetic texts only survived because scribes made too many copies for all of them to be burned; and a few scholars think Hebrews may have been written by a woman in the early church. (The possibility intrigues me; Hebrews is the only New Testament letter that does not name any authors. But the use of a masculine grammatical ending in one verse makes the case for female authorship difficult, though not impossible.)

Because we ourselves live in a place and a time where the Bible has become an authorized and sacred text recognized by a majority of American citizens and honored in government rituals (as when public officials are sworn into office with one hand resting on a Bible), and where biblical verses are quoted regularly in political speeches, it is easy for us to read the Bible today as if it was written by and for those in power, or as a text that can be used to authorize the views of those in power in our society. Treating the Bible as a foundational cultural text, we read into it what we expect to find: our own cultural prejudices and values. Thus some biblical passages have been translated or interpreted in ways that permit their weaponization against our most marginalized citizens, in ways that are anachronistic and would even have been offensive to the communities to which the texts were initially written. When you translate radical or subversive texts into the language of Empire, you eventually get Imperial texts.

For example, let’s look closely at two biblical passages that have been put to the purpose of subjugating women and validating rigid gender hierarchy. We’ll look at how these passages—one written in Hebrew in the Old Testament, one in Greek in the New Testament—have been mangled and misunderstood in English, and at what we might find in the original texts. Then, I’ll share some stories of the early church—overlooked stories, nearly forgotten stories, stories that challenge things we think we know both about our past and our present.

The Proverbs 31 Woman

The first of these two passages is Proverbs 31, from a Hebrew wisdom text. Proverbs 31 has been treated as one basis for defining “family values” in some Christian communities in the U.S. In most Christian translations of Proverbs 31, men are told to praise and admire “the virtuous woman” or “the good woman” (or, in a few versions, the “capable woman” or the “capable wife”). But the Hebrew eshet chayil does not mean “virtuous woman.” It means “woman of valor.” (Jewish translations into English, such as the JPS, get this right.)

In his annotations to The Hebrew Bible, Robert Alter parses the word like this: “…vigor, strength, worth, substance. It is a martial term transferred to civic life.” He also notes the word shalal (“prize, loot”) in the line that follows: “The heart of her husband trusts her / and no prize does he lack” (Proverbs 31:11). It is as though the woman of valor is being compared to a victorious warrior returning home with spoils after war. (In fact, in this metaphor, the husband is the one awaiting the spoils-laden return of the warrior who has his heart; the gender roles a modern reader would expect are flipped.)

In our English Bibles, we often get “virtuous,” “good,” or other adjectives suggestive of moral character because the translation committee commissioned by King James I four centuries ago translated eshet chayil in this way. Because that Authorized Version became our sacred text, future committees have dutifully followed suit. But in the seventeenth century, the word “virtuous” made somewhat more sense; the Victorians hadn’t yet gotten their hands on the word (and wouldn’t for another 250 years). At the time, “virtuous” still suggested the Italian virtù, meaning manliness, purposeful action, and bravery—not moral purity or goodness. Vir is Latin for “man,” and we get from it not only the English word virtue but also virility. The “virtuous woman” in Proverbs 31 is the very same woman whom the King James translation tells us is clothed “in strength and honor,” like a warrior (Proverbs 31:25).

However, the Hebrew eshet chayil doesn’t suggest manliness or masculinity. It suggests valor. The woman of Proverbs 31 is brave, persistent, audacious, resourceful, and ready for anything. In that chapter, we find her running a business. We find her planning for the future, charting a course toward her dreams. A more apt translation of eshet chayil into contemporary English may well be “a daring woman.” Or at least, we could adopt the Jewish translation and go with “valorous woman”; it is far more accurate.

What I want us to notice is the wide gap between the “daring,” bold woman and the “virtuous,” well-behaved woman. This gap persists in our modern Bibles for two reasons. First, the fact that the meanings of many words have shifted dramatically over the past four hundred years, so that words that meant one thing to the readers of King James’ 1611 Authorized Version often convey something completely different to us now. Second, we bring with us into the Bible, eisegetically, a bias from our own culture and our religious tradition, an expectation that in those pages we will find meek, submissive women—and instructions for women to be subservient beings. In reality, little of that is in the text. That’s in us; we bring it with us when we translate or read the book. We insert it because we expect it. And once it’s there, it gets used within our religious communities to justify and reinforce a subjugation and marginalization of women that may be faithful to the nineteenth-century Victorian ideal of “the angel in the house” but that is unbiblical and anachronistic. I wish to remind my fellow Christians: you and I, we did not become Christians to learn from the Victorians or to run our households in the Victorian way. That’s not why we’re here.

About the Author

Stant Litore is the author of the nonfiction titles Lives of Unstoppable Hope, Write Characters Your Readers Won’t Forget, Write Worlds Your Readers Won’t Forget, and the fiction titles Ansible, The Zombie Bible, Nyota’s Tyrannosaur, and Dante’s Heart. Best known for his weird fiction, alternate history, and science fiction, he holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Denver (as Daniel Fusch) and has served as a developmental editor for Westmarch Publishing. His doctoral research was on the epistemology of wonder in early modern religious ceremonies and theater. His fiction has been acclaimed by NPR, has served as the topic for scholarly work in Relegere and Weird Fiction Review, and he has been hailed as “SF’s premier poet of loneliness.” He is fascinated by ancient languages, history, and religious studies. He lives in Colorado with his wife and three children and is working on his next book.

__________________________________________

Upon purchase, you will be able to download a MOBI or EPUB ebook file.

Please consider tipping the author.

Recommended from this author:

Check out The Zombie Bible (fiction).

| Status | Released |

| Category | Book |

| Author | Stant Litore |

| Genre | Educational |

| Tags | Historical |

Purchase

In order to download this ebook you must purchase it at or above the minimum price of $7.99 USD. You will get access to the following files: